The first thing to recognize is that Denmark, like the other Nordic countries, has quite a free-market economy, apart from its welfare state transfers and high government consumption. The Nordic countries tend to get rather high rankings on global measures of economic freedom. Denmark is thus number 22 on the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) index and number 11 on the index published by the Heritage Foundation.1 Denmark ranks at number 3 on the World Bank’s Doing Business report, which assesses the ease of doing business around the world.2

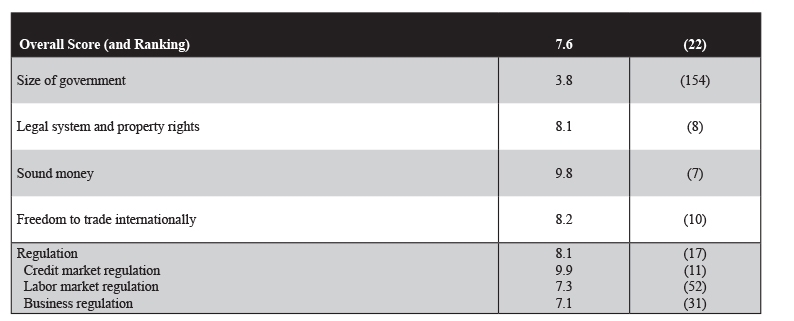

Table 1. Economic Freedom in Denmark, Ratings and Rankings (maximum rating 10.0)

Source: James Gwartney, Robert Lawson and Joshua Hall, Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2015)

Table 1 shows the Danish scores on the five sub-indices of the EFW index. High tax revenues, marginal tax rates, and government spending related to the welfare state earn Denmark a very low rank on those “size-of-government” measures. On the other indicators, however, Denmark scores quite high, in some cases in the top ten. Its ratings on the protection of property rights and the integrity of the legal system are very high by international standards, as is the soundness of its monetary system (with the Krone having been pegged to the Euro or the Deutsch Mark for more than 30 years). Being a small country very dependent on the international division of labor and comparative advantage, Denmark has a long tradition of free trade with the outside world (nowadays the trade regime is to a high degree determined by the European Union). With respect to regulation, Denmark scores quite well. Credit markets are among the less regulated internationally. During the recent financial crisis, tax payers did not have to subsidize banks, and some banks were allowed to fail. The Danish labor market is very flexible: there is no legislated minimum wage, and there are few restrictions on hiring and firing. The overall labor market score on the EFW is, however, dragged down by the existence of conscription. Finally, Denmark is the least corrupt country in the world according to Transparency International.3

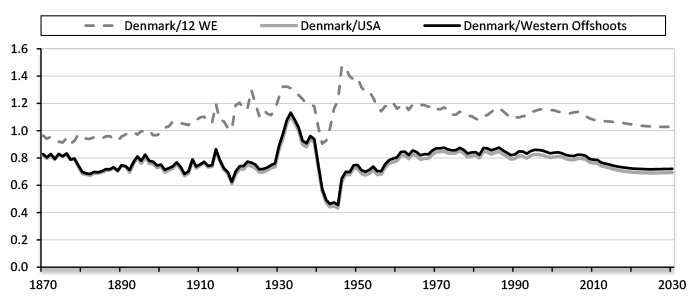

Second, Denmark did not become a rich country recently. As Figure 1 shows, Danish per capita GDP relative to other countries reached a maximum 40 to 60 years ago (ignoring the “noise” from the Great Depression and World War II). Denmark caught up to and overtook “old Europe” in the fifties, while it narrowed the gap with the United States and other Western offshoots until the early 1970s, when the process of catching up came to a halt. Danes are still not as rich as Americans.

Figure 1. Danish Per Capita GDP Relative to Other Countries

Source: Angus Maddison, Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1-2008 AD, 2008, available at: http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm.

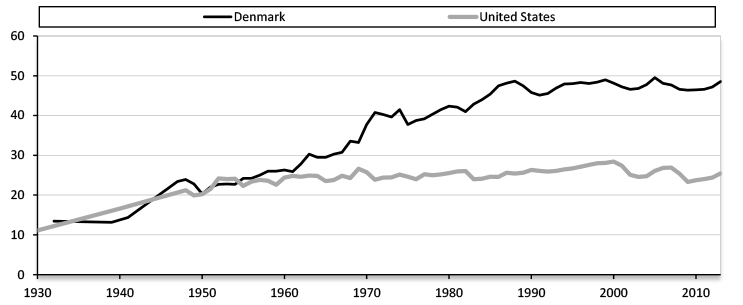

At the time Denmark became rich relative to the rest of the world, it was not a welfare state. In fact, Denmark has historically been a low tax country by international standards (see Figure 2). Until the 1960s the ratio of Danish tax revenue to GDP was the same as in the United States and lower than in Great Britain. The sharp divergence in the Danish tax level really occurred in the second half of the 1960s, when first a left-wing coalition government and then a right-wing one increased the tax-to-GDP ratio by some ten percentage points. Interestingly, government spending was to a large extent driven by increases in tax revenue stemming from the introduction of a value-added tax and withholding taxes on wage income.

Figure 2. Historical Tax Burden

Note: The Danish series has data break in 1947 and 1965, the American in 1948 and 1965.

Source: OECD Tax Databse, “Fiora consolidated govt revenue,” Whitehouse.gov, taxfoundation.org, “Økonomisk vækst i Danmark” - Svend Aage Hansen, “Beskatning i Danmark” - DST 1987, and own calculations.

The 1970s saw a strong tax revolt, as Mogens Glistrup’s newly formed Progress Party became the second largest in the 1973 “landslide” election. Nevertheless, spending kept growing as the welfare state attracted new clients and new programs were added, the economic crisis lead to increasing unemployment, and attempts were made to combat the crisis by increasing fiscal expenditures. By the early 1980s the economy was in very bad shape, with high unemployment, a huge and widening government deficit, and serious concerns over the large external deficit. All governments since the right-wing government, which came to power in 1982, have implemented structural reforms of the welfare state and tax system, reducing welfare state “generosity” and cutting marginal tax rates, as well as consolidating public finances.

So, Denmark first became rich, and then introduced the government programs that make up the welfare state. The huge increase in government spending has been accompanied by deep structural problems, which has made it necessary to reform the Danish economy and welfare state. It can hardly be claimed that introducing the welfare state made Denmark rich; rather it was the other way around. Denmark first became rich, and then the authorities began to redistribute some of the wealth.

But what about Denmark’s apparent happiness? Maybe material wealth doesn’t matter that much if you are satisfied with your life. In fact, life satisfaction and income are highly correlated both across country averages and across individuals within a country, as pointed out in a comprehensive study of the literature by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers.4(The 2015 Nobel laureate in economics, Angus Deaton, has made the same point.)5 They reject the so-called Easterlin Paradox, which posits that in the long run increased income doesn’t correlate with increased happiness (and that saw only a between- and not a within-country correlation), and thus could be interpreted as a case for redistribution. If redistributing from the rich to the poor didn’t make the rich less happy, redistribution could increase “gross national happiness.” And in that case, welfare state redistribution could be the reason for the Danish world record in self-reported happiness.

Alas, Denmark is no longer the happiest country in the world, having been overtaken by the low-taxed Swiss in the latest survey.6 More important, as already mentioned, the Easterlin Paradox is not supported by the literature. The Danes’ high happiness level is probably due to their high income level. Furthermore, as pointed out by Christian Bjørnskov, a high level of trust also seems to increase life satisfaction, and, as Danes are quite trustful, that might play a role here too.7 Again, the high level of trust preceded the welfare state in Denmark rather than being caused by it.

In many respects, Denmark could serve as a model for the world. But if you fail to learn the right lessons, it could be dangerous to try to imitate our model, especially the idea that you can become rich by redistributing wealth or that there is a gentler, more successful way to socialism than the one experienced by typical socialist countries.

And it would certainly be ironic if the Danish case were to become an excuse for politicians in the United States, Greece, or other countries to avoid fiscal consolidation and economic reform, since we Danes have been reforming and consolidating for decades to deal with the problems created by the introduction of our welfare state.

Notes

1. James Gwartney, Robert Lawson and Joshua Hall, Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2015), co-published in the United States by the Cato Institute.

2. World Bank, Doing Business 2015: Going Beyond Efficiency (Washington: World Bank, 2014).

3. Transparency International, 2014 Corruption Perception Index (Berlin: Transparency International, 2014).

4. Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, “Subjective Well – Being and Income: Is There Any Evidence of Satiation? American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 2013, vol. 103, no. 3, pp. 598-604.

5. Angus Deaton, The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 18, 21.

6. John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, and Jeffrey Sachs, eds, World Happiness Report 2015(New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2015).

7. Andreas Bergh and Christian Bjørnskov, “Historical Trust Levels Predict the Current Size of the Welfare State,” Kyklos International Review for Social Sciences, vol. 64, issue 1 (February 2011): 1-19.

Otto Brøns-Petersen is the director for analysis at the Center for Political Studies (CEPOS), a think tank in Denmark.

The above was first posted on December 31, 2015 at Cato.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment